Geometric art looks simple at first glance—circles, triangles, grids—but it can carry surprising depth, from strict mathematical order to optical tension and cultural symbolism.

This article explains what geometric art is, how it developed, what makes it visually effective, and how it shows up today in design, architecture, and digital tools.

What Geometric Art Is, and Why It Feels “Clear”

Geometric art is visual work built primarily from basic shapes and their relationships: straight lines, arcs, polygons, repeating tiles, and structured compositions. The appeal often comes from clarity. A triangle reads faster than a complex figure; a grid organizes space so the eye knows where to go. That legibility is one reason geometric art has been used for everything from sacred decoration to corporate logos.

At its core, geometric art depends on rules—sometimes explicit, sometimes intuitive. Artists may use symmetry, rotation, reflection, and translation (sliding a shape across a surface). A common strategy is repetition with controlled variation: a motif repeats, but scale, color, or spacing changes in small steps, producing rhythm without chaos.

It also sits on a spectrum between representation and abstraction. Some works are purely non-objective, meaning they depict no recognizable subject. Others use geometry to simplify reality: a city skyline reduced to rectangles, a face suggested by a few angled planes, or a landscape organized into bands.

A Brief History: From Ornament to Modern Abstraction

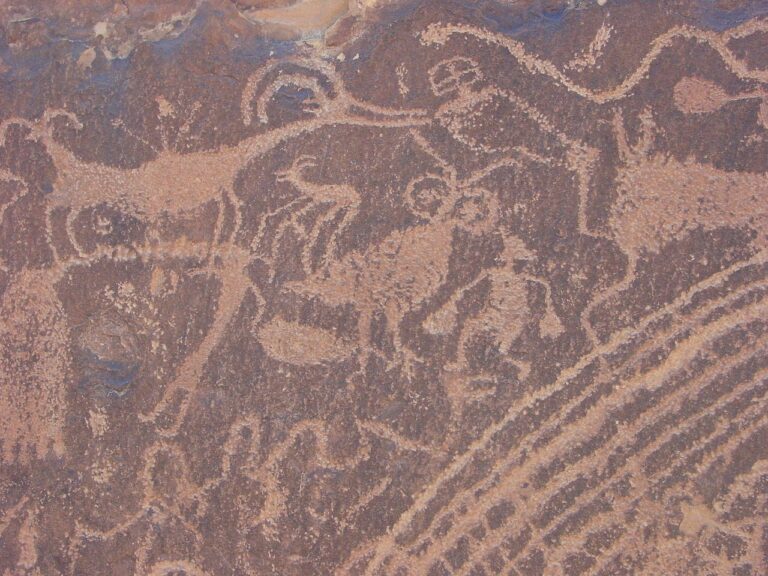

Geometric patterns appear across many cultures because the tools and constraints of making often push artists toward geometry. When you carve stone, weave cloth, lay tiles, or cut wood, straight lines and repeated units are efficient and durable. This practicality feeds aesthetics: repeated shapes become pattern, and pattern becomes meaning.

One major historical thread is architectural ornament. Tessellations—patterns that cover a surface without gaps—are prominent in Islamic art, where complex geometric tiling and star polygons demonstrate both craftsmanship and sophisticated pattern logic. The underlying math can be advanced, but the immediate experience is sensory: endless continuity, balanced density, and a sense of order that feels expansive rather than empty.

In the 20th century, geometric art took on a new role as fine-art abstraction. Movements such as De Stijl emphasized reduction and structure, using horizontal and vertical lines with limited palettes to pursue universal visual language. Constructivist approaches treated geometry as a modern, engineered aesthetic. Later, Op Art exploited geometric precision to create optical vibration, making the viewer’s perception part of the artwork.

How Geometry Produces Mood: Balance, Tension, and Illusion

Geometry is not automatically “cold.” Small choices in proportion, spacing, and color can make a composition feel calm, energetic, or unstable. Symmetry tends to read as stable and formal, especially when mirrored across a central axis. Asymmetry can feel modern and dynamic, particularly when a large shape is counterbalanced by several smaller ones.

Numbers matter in practice even when viewers do not consciously calculate them. Repeating a unit 6 or 8 times around a center often produces a decorative “wheel” effect, while 3 or 5 can feel more irregular or pointed. Grids commonly rely on consistent intervals; breaking the interval once or twice can create emphasis the way a drum fill stands out in a steady beat.

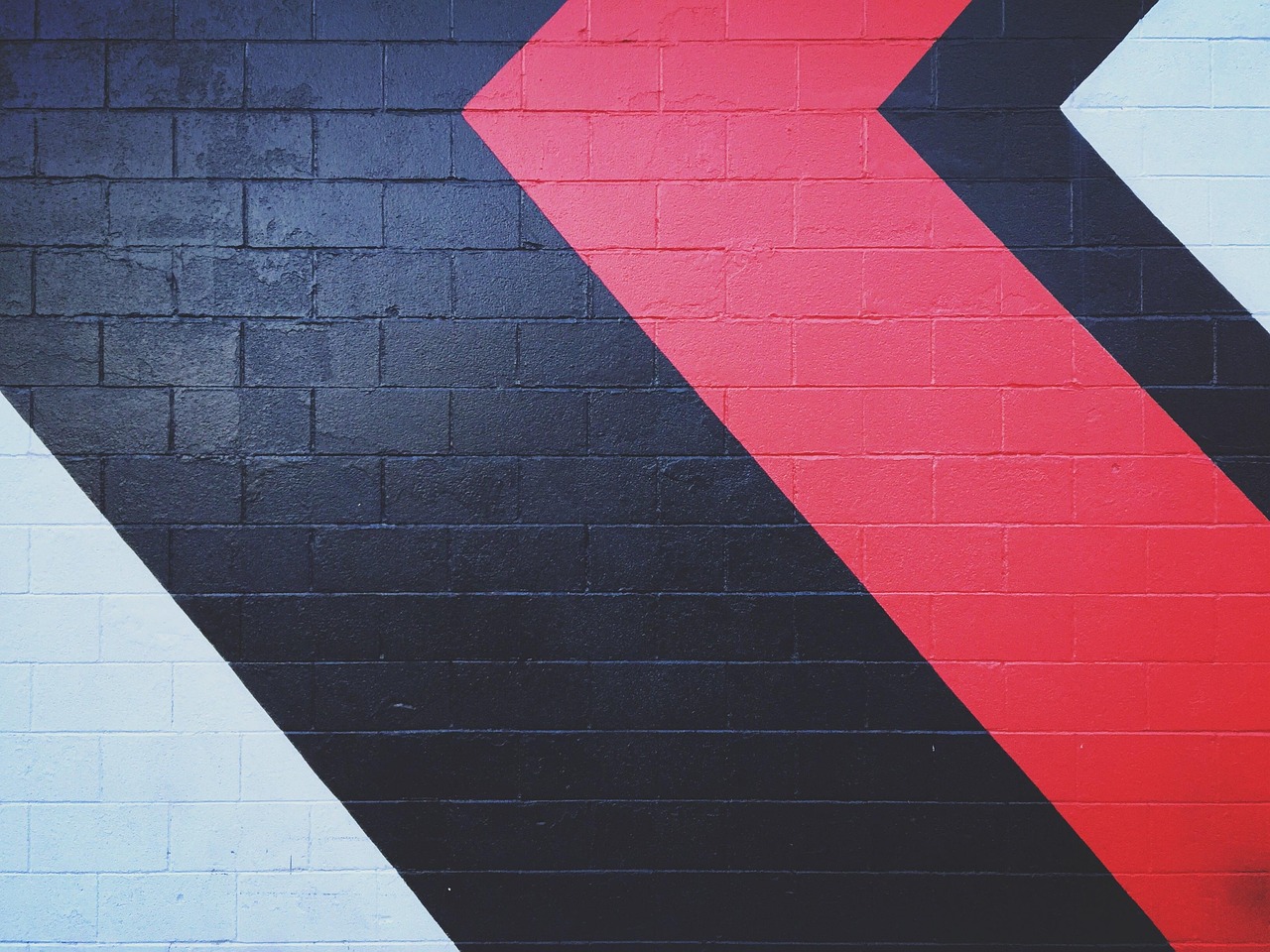

Geometric art also excels at illusion. Parallel lines that slightly converge can imply depth; alternating light and dark bands can make a flat surface appear to ripple. High-contrast edges sharpen these effects because the eye detects boundaries quickly and can be “tricked” into reading motion. This is why many optical works use black and white, then add restrained color for controlled impact rather than decorative noise.

Where Geometric Art Shows Up Today: Design, Architecture, and Digital Tools

In contemporary life, geometric art is everywhere because geometry is a foundational language of visual communication. Logos often rely on circles, squares, and triangles because they scale cleanly from a phone screen to a billboard. Icons and interface systems use grids to maintain consistency across hundreds of symbols. Even when an illustration looks hand-drawn, it may be built on an underlying geometric scaffold.

Architecture and interiors use geometry for both structure and atmosphere. A facade with repeating modules can control light, reduce heat gain, and create identity at the same time. Inside, patterned screens, acoustic panels, and tile layouts turn functional surfaces into visual fields. The modern preference for clean lines also aligns with geometric minimalism: fewer elements, more intention, and clearer hierarchy.

Digital creation has expanded the toolkit. Vector software allows perfect curves and scalable shapes; generative methods use rules to produce thousands of variations from a simple seed. A designer can define constraints—such as “rotate a square by 5 degrees each step” or “increase circle diameter by 2 units”—and quickly explore outcomes. This speed does not replace judgment; it shifts effort toward selecting the most coherent result and refining color, spacing, and contrast.

Conclusion

Geometric art endures because it combines discipline with versatility: simple shapes can build calm symmetry, sharp tension, cultural pattern, or optical surprise, and the same principles translate smoothly from handmade craft to modern digital design.